What Are Hardwood Dowels Made Of? 10 Quick Answers + Wood Rankings

Hardwood dowels are made from kiln-dried hardwood boards that are machined into round rods with the grain running lengthwise. The “hardwood” label describes the tree group (broadleaf species), not how hard the dowel feels in your hand. The USDA Wood Handbook notes that the hardwood and softwood categories are not directly tied to “hardness or softness.”

This guide breaks down the woods manufacturers use, what properties to look for, which species run heaviest, and how to choose dowel rods for clean, dependable hardwood dowelling.

Contents Here

Hardwood dowel rods

Hardwood dowel rods are the long, continuous dowels you buy by the foot (or in standard lengths), then cut to whatever your project needs. Typical offerings run from 1/8″ up to 2″ in diameter, with lengths that can reach 12 feet, depending on the supplier and species.

Here’s what “good stock” looks like when you’re sorting dowel rods at the bench:

- Straight grain with minimal runout. Runout weakens a dowel the same way it weakens a chair rung.

- No knots or dark streaks crossing the rod. Those spots split first when you drive or clamp.

- Consistent diameter end-to-end. A dowel that “necks down” leaves a loose joint.

- Dry feel and stable shape. A fresh, damp dowel swells in the hole and can crack the surrounding wood.

If you need a non-standard diameter, or you want the dowel to match your project wood exactly, making your own is often the cleanest route. This walkthrough on how to make dowels for custom sizes and tight fits covers several simple shop methods.

If you’re new to joinery, start with what a dowel rod is and how it’s used in woodworking before you choose a size or species.

What are the properties of hardwood dowel

The properties of a hardwood dowel come from two things: the wood species and the way the grain runs through the rod. Wood is also orthotropic, which means it behaves differently along the grain versus across it.

These are the properties that matter most in real dowel work.

Density and weight

Density drives how “hefty” a dowel feels, and it tracks with many strength properties. The USDA Wood Handbook notes that mechanical properties vary with moisture content and specific gravity.

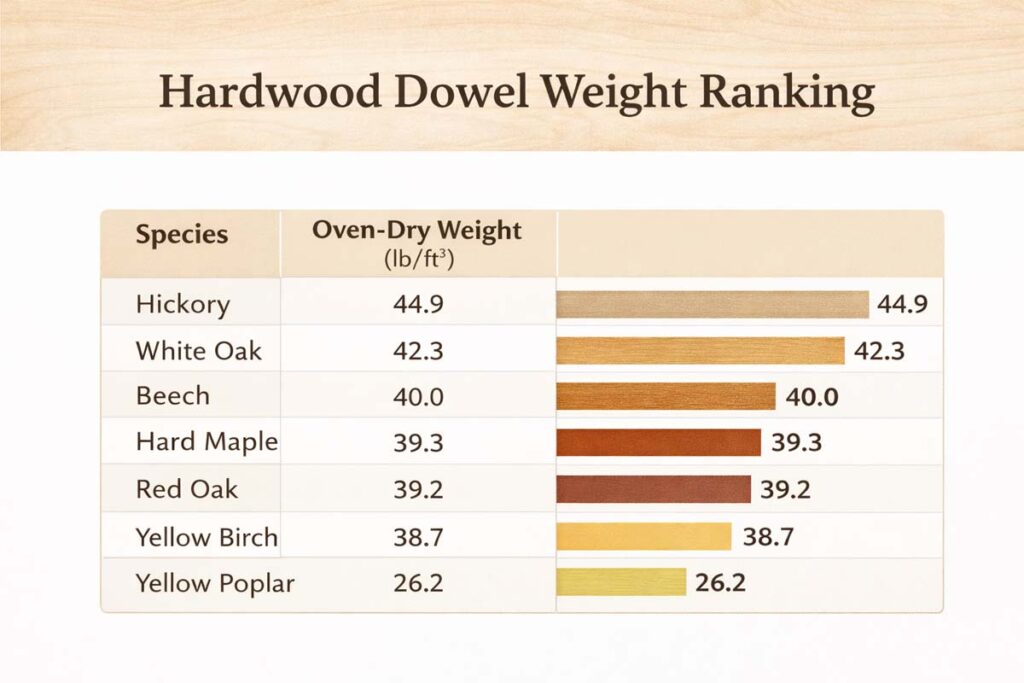

As a practical example, Miles and Smith (USDA Forest Service, 2009) list these oven-dry weights (at 12% moisture-content volume basis) for common hardwoods:

- Shagbark hickory: 44.9 lb/ft³ (specific gravity 0.72)

- White oak: 42.3 lb/ft³ (specific gravity 0.68)

- American beech: 40.0 lb/ft³ (specific gravity 0.64)

- Sugar maple (hard maple): 39.3 lb/ft³ (specific gravity 0.63)

- Northern red oak: 39.2 lb/ft³ (specific gravity 0.63)

- Yellow birch: 38.7 lb/ft³ (specific gravity 0.62)

- Yellow-poplar: 26.2 lb/ft³ (specific gravity 0.42)

If two dowels are the same size, the heavier one is the denser one. That matters for rungs, pegs, and any dowel that sees bending.

Dent resistance (side hardness)

Side hardness is a good “shop proxy” for how easily a dowel will bruise during clamping, assembly, and daily use. The USDA Wood Handbook lists side hardness values for clear, straight-grained wood at 12% moisture content.

A few useful benchmarks:

- Shagbark hickory: 8,400 N (about 1,890 lbf)

- Sugar maple: 6,400 N (about 1,440 lbf)

- White oak: 6,000 N (about 1,350 lbf)

- American beech: 5,800 N (about 1,300 lbf)

- Yellow birch: 5,600 N (about 1,260 lbf)

What this means in plain terms: hickory dowels take the most abuse, then maple, oak, beech, and birch run close behind.

Dimensional stability and moisture movement

A dowel is long-grain along its length, but it still moves across its diameter when humidity changes. That’s why a dowel that fits “perfect” on a dry day can turn into a wedge later.

The Wood Handbook’s moisture guidance points out two practical limits:

- “Dry” lumber is defined at 19% moisture content or less.

- A lot is considered satisfactory if the average moisture content is within 1% of the recommended value and each piece stays within the stated limits.

For dowels, the takeaway is simple: keep your dowels and your project parts in the same space long enough to equalize before you drill and glue.

Glue bonding and dowel geometry

Wood-to-wood dowel strength depends on surface contact, fit, and glue distribution. That’s why fluted dowel pins are so common. A retailer description of hardwood dowel pins notes chamfered ends and “well-formed flutes” that support a mechanical lock and good glue adhesion.

Which hardwood dowels are the heaviest

The heaviest hardwood dowels are the ones made from the densest species. Using oven-dry weight per cubic foot as the yardstick, shagbark hickory and white oak sit near the top among the commonly sold domestic dowel woods.

A practical “shop ranking” for common species (heaviest to lightest, same dowel size):

- Hickory (example: shagbark hickory, 44.9 lb/ft³)

- White oak (42.3 lb/ft³)

- Beech (40.0 lb/ft³)

- Hard maple (39.3 lb/ft³)

- Red oak (example: northern red oak, 39.2 lb/ft³)

- Yellow birch (38.7 lb/ft³)

- Yellow-poplar (26.2 lb/ft³)

To verify please see nrs.fs.usda.gov pdf file.

Two notes from experience:

- Heavier is not automatically “stronger in the joint.” A sloppy hole and a starving glue line fail before the wood species matters.

- Heavier woods punish dull tools. Hickory and oak burn drill bits faster, and they split more readily if the fit is too tight.

Hardwood dowelling

Hardwood dowelling is using dowels as structural pins to align and reinforce joints, often in edge joints, face frames, and chair parts. The wood choice matters, but the joint layout matters more.

Here’s a clean workflow that keeps dowel joints tight without splitting anything:

- Match dowel moisture to the workpiece. Store dowels in the same room as the project parts.

- Drill straight holes with a stop. A drill guide or jig keeps the dowel axis true.

- Aim for a snug slip fit, not a press fit. A dowel that needs hammering can split the stile or rail.

- Use fluted pins when you can. Flutes help move glue and trapped air.

- Apply glue to the hole walls, not only the dowel. This reduces dry spots on open-pored woods.

- Clamp until the joint closes, then stop. Overclamping can bow parts and squeeze out too much glue.

If you want a deeper look at adhesives and glue-up timing, see my guide to choosing a wood glue that plays well with dowel joints.

Choosing a species for the job

Use this as a simple selection rule:

- For chair rungs, pegs, and high-wear parts: hickory, hard maple, oak, or beech give better dent resistance and strength.

- For light-duty jigs and craft work: yellow-poplar is easier to cut and drill, and it’s still a hardwood by classification.

- For visible dowels: maple, birch, and beech tend to finish cleanly and look uniform.

If you’re stuck choosing between common boards you already have on the rack, this piece on how to choose between pine, oak, and maple when strength and workability matter can help you think it through.

A quick inspection checklist before you glue

- Confirm the dowel is straight and round.

- Cut a short test piece and dry-fit it in a scrap hole.

- Check for clean, straight grain along the length.

- Use a sharp brad-point bit to limit tearout.

- Keep clamps and cauls ready before you open the glue.

Hardwood dowels live or die by three things: straight grain, the right moisture level, and a clean fit. Pick a species that matches the job, then spend your time on layout and drilling. That’s where dependable joints come from.

Bottom line

Hardwood dowels are made from kiln-dried, straight-grain hardwood lumber that manufacturers turn into consistent cylinders. Birch, beech, maple, and oak dominate because they machine cleanly and hold a reliable fit. The “best” dowel comes from matching species, controlling moisture, and choosing a tolerance that fits your drilling and glue-up habits.